https://doi.org/10.18593/ejjl.32534

COVID-19 PANDEMIC AN THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION IN BRAZIL BY UNCONSTITUTIONALITY STATE AND MUNICIPAL DECREES

A PANDEMIA DE COVID-19 E AS VIOLAÇÕES DE DIREITOS HUMANOS NO BRASIL POR DECRETOS ESTADUAIS E MUNICIPAIS INCONSTITUCIONAIS

Emerson Ademir Borges de Oliveira1

Jefferson Aparecido Dias2

Abstract: The aim of this paper is a study on Covid-19 pandemic and restrictions that came along. With restrictions, violations. The principle of legality, the basic historical construction of the rule of law, had been solemnly and repeatedly vilified and carried with it many constitutional rights and principles, which, more than indispensable for us, are so on a universal level, such as the restless go and come and exercise economic activity. Under the auspices of teratological decrees, of congenital malformation, our rights were restricted. But what is worse: often under the parsimonious eye of those who should be keeping the Constitution. Is it deference to the political propaganda pieces, based on biopower, that invade the everyday? Is it a fear of contributing to health discouragement, justifying non-legality? In this paper, more than addressing the unconstitutionality of restrictions, we propose to discuss the reasons for this passivity and acceptance. Methodologically, we use inductive guidance, choosing some characteristics as a starting point to build a broader conclusion, using a wide bibliographic and jurisprudential review.

Keywords: biopower; unconstitutionalities; Covid-19; limitation of rights; deference.

Resumo: O objetivo deste trabalho é estudar a pandemia de Covid-19 e as consequentes restrições a direitos. Com as restrições, as violações, o princípio da legalidade, a construção histórica base do Estado de Direito, foi solene e reiteradamente vilipendiado e consigo muitos direitos e princípios constitucionais, os quais, mais do que imprescindíveis para nós, assim o são em um plano universal, como o remansoso ir e vir e o exercício de atividade econômica. Sob a batuta de decretos teratológicos, de má formação congênita, nossos direitos foram restringidos. Mas o que é pior: muitas vezes sob o olhar parcimonioso daqueles que deveriam guardar a Constituição. Será deferência às peças propagandísticas políticas, baseadas no biopoder, que invadem o cotidiano? Será receio de contribuir com o desalento da saúde, a justificar a não-juridicidade? Neste artigo, mais do que abordar a inconstitucionalidade das restrições, propomo-nos a discutir os porquês dessa passividade e aceitação. Metodologicamente, emprestamos o direcionamento indutivo, elegendo algumas características como ponto de partida para edificarmos uma conclusão mais ampla, valendo-nos de ampla revisão bibliográfica e jurisprudencial.

Palavras-chave: biopoder; inconstitucionalidades; Covid-19; limitação de direitos; deferência.

Recebido em 30 de janeiro de 2023

Avaliado em 16 de novembro de 2023 (AVALIADOR A)

Avaliado em 27 de outubro de 2023 (AVALIADOR B)

Aceito em 21 de novembro de 2023

Introduction

The aim of this paper is to analyze why decrees limiting fundamental rights are being adopted by the Heads of the Executive Branch (especially from States and Municipalities) and maintained by the Judiciary, despite their unconstitutionalities.

The Rule of Law finds at its base a premise historically built: the principle of legality. From medieval times and the Magna proposal to the revolutionary essays of the eighteenth century, there was a concern to guide us, that of establishing limits to the rulers, so that rights could be formally delineated and become immune to arbitration.

This same concern led to constitutionalism and the election of a representative to act on behalf of the people, the Parliament, the one that really was sovereign, that is plural, heterogeneous and deliberative. The laws did not provide a guarantee of continuity, but a certainty that only by this sovereign could they be approved. And above them, the constitutionalization of rights established certain limits to direct legislative work.

This is the context that justifies the Rule of Law in itself: one must have the full conviction that the Constitution is a sovereign guarantee and limiting instrument. And, even in the spaces where its restriction is allowed, this limit requires a law, approved and discussed by Parliament. More modernly, even when there was a constitutional violation, one would resort to the Judiciary to guarantee the custody of the Constitution.

It is true that the year 2020 presented us with a sordid, cruel and unpredictable reality. But it is precisely in crises that attention to guarantees is called with greater emphasis, especially this very old one: that the State must be configured by law.

Our reality, however, had been presented differently. In the name of sanitary measures, clear constitutional violations, with decrees establishing more than doubtful restrictions on such expensive fundamental rights. And the question is: why this passivity? Why are we allowing these violations?

Had they occurred in the distant past, such violations would be due to absolute power, which finds no limits except in the will of the government, but, currently, unconstitutional decrees can be recognized as security devices, adopted by biopower.

Using an inductive method and drawing on extensive bibliographic and jurisprudential research, we intend to demonstrate that such decrees have been adopted not as normative acts per se, but as part of an advertising campaign that, even if supposedly motivated by the best of intentions, clearly results in violations of principles that are quite dear to us. In addition, these violations of principles are only possible and the decrees have been considered valid in view of the posture adopted by the organs of the Judiciary.

1 The constitutional emergence of principle of legality

The principle of legality is, without doubt, the basis of the rule of law. Although it was not expressly provided for in the Magna Carta, even in 1215, its very existence is a consequence of the principle, given the fact that the main claim of the English barons in the face of King John Lackland was the existence of a safe forecasting instrument about limitations on rights, especially property and freedom, with stipulations on taxation, prosecution and imprisonment (Borges, 2020, p. 81).

Do not forget, however, that, in its item 45, the Carta foresaw that magistrates and other justice agents would only be appointed if they knew and faithfully observed the laws of the Kingdom of England. In addition, item 39 established the legitimate judgment by peers or by the laws of the country, while item 55 made null the fines imposed against the laws of the country.

The definitive rise of the principle of legality, however, took place in the revolutionary context of the eighteenth century, in which, at first, it was sought, precisely, the protection of the citizen in the face of state arbitration, establishing limits to the State’s performance, which in passing, it was based on the establishment of rights.

In traditional constitutionalism, the 1789 Declaration of Human and Citizen Rights, later incorporated into the 1791 French Constitution, already emphasized that a society in which there was no guarantee of rights and separation of powers would not have a constitution. (art. 16).

Article 4 of the Declaration, when dealing with freedom, asserted that it would consist in the realization of what did not affect the rights of other men, which could only be determined by law. The law, once again, appears prominently in terms of social functioning, since, by the security it provides, it may establish the limits between individual rights.

The separation of powers as one of the pillars of constitutionalism (Borges de Oliveira, 2015, p. 91), combined with the establishment of rights, presupposes, from the perspective of legality, two great purposes. The first is that the limitation must be by law. The second is that the responsibility for the law is found in the sovereignty of the Parliament33, precisely ensuring to the pluralism of the Legislative House what cannot be guaranteed in the individuality of the Executive.

When the ruler was submitted to the law, the meaning reproduced is that no one is above the law and the State itself is limited to it, as well as anyone who comes to exercise one of the powers of the Republic, Legislative, Executive or Judiciary. On the other hand, the citizen is guaranteed by the principle of legality that he will not be obliged to do or fail to do anything that is not provided for by law (Borges, 2020, p. 81).

The formula, transcribed in article 5, II, Brazilian FC, is not even new among us, nor is it attributed to Parliament. The Constitution of the Brazilian Empire, of 1824, repeated the provisions of article 179, I, as well as article 153, paragraph 2, of Constitutional Amendment 1/1969, resulting from the most critical moment in the national democratic context.

Not even the infamous item 15 of article 122 of the Brazilian Constitution, of 1937 (“A Polaca”) got missed, clarifying the need for the “law” so that the limits to fundamental rights, such as prior censorship, were established, without arguing, at this point, its possibility. What we call attention to is the fact that even in the darkest moments of constitutional history, the law, an assumption of the rule of law, has always been present. Sometimes, even entering spheres that it could not regulate, sometimes as an instrument of democratic deviations. But the law, since constitutionalism became science, is a maxim.

It is in this design that it seems unimaginable that we shy away from legality, today, to establish limits on rights, to restrict citizens or even companies.

Rather, it must be borne in mind that, even when it comes to fundamental rights that establish prima facie priorities, despite the fact that they cannot be rigidly hierarchized, such as legal freedom and equality, in Alexy’s (2002, p. 549-550) construction, possibility of giving in to other rights or principles, and of suffering limitations. Only, in prima facie cases, the argumentative force must be more solid, but always from a perspective of flexibility or “soft order” of rights (Borges de Oliveira; Ramos Júnior; Dias, 2017, p. 52).

In dealing with the limitation on property rights, the German Constitutional Court emphasized that Article 14 of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz) assigns to the legislator the “task of determining the content and limits of ownership”. “In this way, the legislator creates, at the level of the objective law, those legal proposals that justify and shape the legal status of owner”, being able to contextualize specific groups or even establish hypotheses of loss of property, as long as the consolidated legal situations are maintained4.

The fact is that there is no fundamental right immune from restrictions, as recapitulated by the Brazilian Court, for example, in MS 23.4525. In fact, not even the right to life, according to ADPF 546, or freedom, in the wake of criminal law.

However, it should be noted, however, that there are two major assumptions for limiting constitutional rights: a) that they are made by law; b) the existence of limits to the limitation, that is, the “limits of the limits”; themes which we will now expose.

2 The limitation of fundamental rights

One of the richest works on the restriction of fundamental rights was developed by the German teachers Bodo Pieroth and Bernhard Schlink (1995, p. 77-78), who established a series of questions about the constitutionality of the restrictive law.

From Mendes’s (2007, p. 107-108) adaptation, the questioning table - constitutionality test - is as follows:

I - Is the conduct regulated by law included in the scope of protection of a certain fundamental right?

II - Does the discipline contained in the law constitute an intervention within the scope of protection of fundamental rights?

III - Is this intervention justified from the constitutional point of view?

1. Are the basic rules on legislative competence and on the legislative process observed in drafting the law?

2.

a) in the individual rights submitted to qualified legal restriction: does the law satisfy the special requirements provided for in the Constitution?

b) rights subject to simple legal restriction: does the law affect other individual rights or constitutional values?

c) in individual rights not subject to the express legal restriction: is there a conflict or collision of fundamental rights or between a fundamental right and another constitutional value that can legitimize the establishment of a restriction?

3. Does the restriction comply with the ‘parliamentary reserve’ principle?

4. Does the restriction comply with the proportionality principle?

4.1 Is the restriction adequate?

4.2 Is the restriction necessary? Are there less burdensome means?

4.3 Is the restriction proportional in the strict sense?

5. Has the essential core of the fundamental right been preserved?

6. Is the law sufficiently generic or does it appear to apply only to a specific case (case law)?

7. Is the restrictive law sufficiently clear and determined, allowing the affected person to identify the legal situation and the consequences that result from it?

8. Does the law satisfy other standards of constitutional law, including those relating to the fundamental rights of third parties?

When it comes to the restriction of rights, it should be noted that the questions themselves start from a common place: the law. That is to say, although the limitation of rights is possible - if the test has passed - there is an inescapable first step: the legal limit, that is, the restriction was built by legislative means. And only for her. In fact, as will be seen later, the principle of legality as a starting point will be found, equally unattainable, when the limitation occurs by a concrete act.

Regarding the theme, Gomes Canotilho’s (2007, p. 729) statement is irrefutable:

A notable change in the meaning of the law reserve can be seen in the law-fundamental rights relational scheme. Initially, the reserve of law was understood as “reserve of freedom and property of citizens”. The general reserve of law was primarily intended to defend the individual’s two basic rights - freedom and property. In the current constitutional context, this scheme is no longer an acceptable construction. First, the reservation of the law within the scope of fundamental rights (maxime within the scope of rights, freedoms and guarantees) is directed against the legislator himself: only the law can restrict rights, freedoms and guarantees, but the law can only establish restrictions observing the constitutionally established requirements. Hence the relevance of fundamental rights as a determining element of the scope of the law reserve.

In the same sense, Garcia de Enterría (1988, p. 6) teaches:

[...] as to the content of the laws, to which the principle of legality refers, it is also clear that any content (dura lex, sedelex) is not valid either, it is not any normative command or precept that is legitimate, but only those that take place “within the Constitution” and especially according to their “order of values” that, with all clarity, express and, mainly, that do not pay attention, but that instead serve fundamental rights.

First, do not forget, as is common in the field of fundamental rights, its principle nature, calling for the analysis of the question from the perspective of optimization, characterized by being satisfied in varying degrees and the fact that the due measure of your satisfaction does not depend only factual possibilities, but also legal possibilities (Alexy, 2002, p. 90).

In addition, if the interpretation constitutes a reduction in the scope of a constitutional provision, it should be assessed whether there is an offense against the essential core of the law.

The imposition of restrictions on fundamental rights must always observe the idea of limitation. The theory of immanent limits or limits of limits (Schranken-Schranken) was built under the justification of parameterizing the legislator in the restriction of individual rights. “These limits, which stem from the Constitution itself, refer both to the need to protect an essential core of fundamental law and to the clarity, determination, generality and proportionality of the restrictions imposed” (Mendes, 2007, p. 41).

In reality, what is intended is to immunize fundamental rights to the legislator’s action, which could end up emptying the content of those through legislative restrictions. To this end, the principle of proportionality (Verhältnismässigkeitsprinzip) acts properly, especially to assess the adequacy (Geeignetheit) and necessity (Erforderlichkeit) of the legislative act (Mendes, 2007, p. 46).

The operability of the principle, at this moment, is directed not at the legislator, but at the interpreter, especially the Judiciary. As an exercise, it remains to question the interpreter if the interpretation conferred would not have invaded the essential nucleus of fundamental rights or another constitutional precept.

In other words, did the result of the judicial interpretation collaterally end up invading the essential space of any right?

It is true that the adoption of such measures anchored in the rational foundation of jurisdictional decisions, in terms of constitutionality control, does not guarantee the legal integrity of the Supreme Court sentences, especially in view of the interpretative space and the ambiguous or dubious distortions. But it is also true that the submission of subjectivism to rules of control - in any Power - minimizes the chances of invasion of functions by other Powers.

Pieroth and Schlink also propose the constitutionality test of a concrete measure of the Executive or Judiciary Power, which restricts fundamental rights, which is thus designed, based on Mendes’ (2007, p. 107-109) adaptation:

I - Does the conduct affected by the measure fall within the scope of protection of any fundamental right?

II - Does the measure constitute an intervention within the scope of protection of fundamental rights?

III - Can the measure be justified on the basis of the Constitution?

1. Is there a legal basis compatible with the Constitution for the measure?

2. Is the measure itself constitutional?

a) Does it apply the law in accordance with the Constitution?

b) Is it proportional?

c) Is it clear and determined for the affected person?

The issue comes close, at this point, to the central theme of this work, as, as will be seen below, the restrictions operated, in practical terms, by concrete acts of the Executive Power, and not by law.

But, it should be noted that, in this case, the law is again an assumption, that is, there is a legal permissive that allows the Executive Branch to regulate the limitations established in the legal scope. It should be stressed: regulating, not establishing your own restrictions. Hence the question III.1: “Is there a legal basis compatible with the Constitution for the measure?”

Notice how the tests of tedescent professors are built in an essential sequence: a) the law establishes the restriction and this law must be tested on the constitutionality of the restriction imposed by it; b) the law is made effective by regulation of the Executive Branch for the purpose of detailing, provided that it does not distort the very law that brought the permissive nor the Constitution.

What we have in Brazil today is done in violation of these guidelines. As will be seen, there are no laws for the limitations imposed, violating the principle of legality and the Constitution from the outset - for wielding the principle as a fundamental right, in addition to the minimized substantial rights themselves - and, in some cases, there are damage to the essential nucleus of law, surreally operationalized by decrees.

It should be noted, by the way, that the Tedesca construction is the best extraction of the basic differentiation between primary and secondary normative acts and the function of constitutionalism, which cannot be overlooked in times of crisis. Rather, it is precisely when it should be given the most attention.

3 The Brazilian legal situation in the COVID-19 pandemic: unconstitutional raptures

Never before in the history of Brazilian constitutionalism had the Constitution been so vilified by one of the Powers - the Executive -, under the passive eye of the one who had been given the task of protecting it - the Judiciary.

Incumbency, incidentally, that was not attributed without an enormous purpose and a wide justification, when Hans Kelsen’s intellect was victorious over Carl Schmitt’s Constantian proposal, for whom the head of state should be the guardian of the Constitution (HüterdefVerfassung) in the exercise of moderating power (Borges de Oliveira, 2017, p.11), so severely criticized by the former (Kelsen, 2007, p. 243).

Under Kelsen’s (1931, p. 576-628) understanding, in the writings Wer sol der Hüter der Verfassung sein?, the control of the Constitution has a logical premise: “such control should not be entrusted to one of the bodies whose acts must be controlled”, because “nobody should be a judge in his own cause” (Kelsen, 2007, p. 240). Of course, much of its conclusion stems from the fact that it attributes to the Judiciary the role of being the least political among the Powers - and it should remain so, especially when it acts as a negative legislator.

The design, nevertheless, came to sediment the illuminated building with the Austrian Constitutional Court (Verfassungsgerichtshof), of 1920, to break with the diffuse North American model and to “concentrate” the guard of the Constitution in an organ that had such purpose as its principal, although not exclusive, and which, influenced by Parliament’s sovereignty, opted for the path of annulability (Borges de Oliveira, 2017, p. 23-24).

We inherit this sovereignty by virtue of Constitutional Amendment 16/1965, to modify the Brazilian Constitution of 1946, and insert point k in article 101, I, conferring jurisdiction on the Supreme Federal Court to judge the “representation of unconstitutionality of law or act of nature normative, federal or state, sent by the Attorney General of the Republic”, in addition to the dexterity of the judicial review provided since the Constitution of 1891 (art. 59, §1,b) and extraordinarily enlarged by the 1934 text.

The fact is that the Brazilian peculiarity, in spite of any other criticisms, leads to a substantial element in this process: any organ of the Judiciary can act in the face of violations of the Constitution, whether monocratic or plural (art. 97, CF), although the final word falls to the Federal Supreme Court.

In the pandemic context, decrees of the Heads of the Executive Branch were swarming, especially at state and municipal levels.

It should be noted, for the sake of understanding, that the uproar was inaugurated with Federal Law 13,929 / 2020, which brought important definitions about coping measures, such as quarantine and isolation, but committed a very serious legal error, by allowing that, by authorization in an Ordinance of the Ministry of Health, local health managers - not even the heads of the Executives - could implement the necessary restraint measures. In regulation, Federal Decree 10,282 established the list of public services and essential activities, which would later be simply abandoned by most states.

Repeat so that there is no misunderstanding: a law provided that a Ministerial Ordinance would allow health managers to establish, by any means, restrictions on fundamental rights (!!!)

From then on, atrocious creativity begins, sponsored by abuse and by the authoritarian strand, redesigning, in the state and municipal spheres, the fundamental rights, by means of, it is stressed, secondary normative acts.

The first fully attacked right was “to come and go”, so well outlined by the precise wording of article 5, XV, CF: “it is free to move around the country in times of peace, and anyone, under the law, enter, remain in it or leave it with your goods” (Borges, 2020, p. 96).

Think that, in reality, we are only maintaining in the Brazilian Constitution one of the most traditional rights in the constitutional field, also recognized under the universal plan, as in the case of article 13.1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 12 of the International Covenant of Rights Civil and Political Rights and Article 22 of the American Convention on Human Rights.

“Free locomotion or permanence is one of the most important rights of the rule of law and democratic states, like ours, because it is embodied in one of the greatest expressions of the freedom of individuals: to be able to go where, how and when you want”.

It should be noted that, in order to protect it, the constitutional text itself already needed the exception: locomotion will not only be free when we are out of “times of peace”, that is, in war or foreign armed conflict. And no, that does not include a pandemic, not necessarily.

Together came the limitation of economic freedom, inscribed in free initiative and the free exercise of professional and economic activities (article 1, IV; 5, XIII; 170, caput, IV and single paragraph; in addition to other indirect devices), easily seen due to opening restrictions, type of trade, opening hours and even total closing - lockdown. And, perhaps, something worse than that: total insecurity for those who are already anchored in the principle of otherness - business risk -: not knowing when to open or when to close!

Just to remind you of some grotesque Brazilian examples highlighted in the previous text: a) ban on entry into the municipalities, which “won”, with such measure, the status of sovereigns; b) prohibition that certain people, such as the elderly, use public transport, establishing different categories of citizens - in reverse; c) closure of the intercity bus terminal and certain roads for traffic; d) prohibition on the use of maritime beaches - which belong to the Union - by the Municipality; e) prohibition of certain people from circulating on the streets; f) reframing of essential services, differently from that outlined by the Union or the States; g) absence of tangible justifications for considering that a given service can remain open to others, theoretically of less or equal risk; g) and criminal threats to those who dare to break the impositions (Borges de Oliveira, 2020). And until recently: stipulation of a bold plan, divided into five stages, the State being responsible for defining which stage each of “its” municipalities falls into.

The main problem: all this done by Decrees, without any legal basis; the most complete inversion of the meaning of the principle of legality, in which decrees establish the restrictions that must be obeyed as laws.

It is worth using the expressions of Sepúlveda Pertence (ADI 1.923) and Ayres Britto (ADI 3.232): they are “stoned”, “crazy”, “insane” unconstitutionalities.

The uproar, however, did not stop, because the Judiciary, often called, did not always defend the Constitution. In some, it is said, it moved in an antagonistic way and allowed monocratic decisions to spread, diffuse and contradictory, instead of remedying the injury.

In the judgment of the precautionary measure in ADI 6,341, the Supreme Federal Court understood that States and Municipalities would have autonomy to decide on coping measures. Subsequently, however, only in sparse monocratic decisions did it save the Municipalities from the violations perpetrated on the Binding Precedent 387 by the States themselves when they established rules for closing trade valid for all localities. The decision granted, for example, to the Municipality of Londrina, in the State of Paraná, in Claim 40.342, did not safeguard Parnaíba, in Piauí, and Limeira, in the State of São Paulo, in Claims 40.130 and 40.366, in an understanding in which it was brought to covers the common administrative competence for health issues.

It should be noted, however, that even the High Court has made assumptions that ignore the fact that such limitations were not enforced by law, unlike Article 5 and the divisions of jurisdiction in Articles 22, 24, 25 and 30 of the Constitution Brazilian. There is nothing to allow, in the name of common competences, to be adopted coping measures that stipulate limits to fundamental rights without the existence of a legal provision and, perhaps, in an affront to the essential nucleus in some cases. This is accomplished from the most primitive lessons of constitutionalism. This is not, as we have warned, a conflict of principles or rights, but a failure by concrete acts, constitutional and legal rules (to a large extent non-existent).

What, in these terms, explains this state of numbness in the face of such serious injuries to the Constitution and the principle of legality? This is what we will discuss in the following topics.

4 The unconstitutional decrees and biopower

As we saw in the previous items, there is no doubt that the Decrees issued due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which ignore the principle of legality and advance the local competences of the municipalities, are riddled with vices that render them useless from the normative point of view. However, despite this, they have been observed by a large part of the population and are kept in force by judicial decisions, starting from the provocation, even by the Public Ministry, which, apparently, is a contradiction.

It seems to us that this is due to the fact that such decrees, in fact, were not adopted as normative acts, but with a propagandistic drive, as if it were a publicity piece. In addition, they ended up receiving the support of authorities who, constitutionally, would have precisely the role of protecting the Constitution against threats or aggressions.

To analyze this picture, we will use the “ethical diamond” proposed by Joaquín Herrera Flores (2009, p. 122), in his book “The (re) invention of human rights”. According to the conductor of Triana, the “ethical diamond” is a methodological metaphor that allows a given legal or social situation to be appreciated by different aspects, among which it offers twelve dimensions, divided into three layers and two overlapping axes. The vertical axis refers to the semantics of human rights (conceptual) and the horizontal axis to the pragmatics of human rights (material), which include the following elements:

Picture 1 - “ethical diamond”

|

CONCEPTUALS: Vertical axis |

MATERIALS: Horizontal axis |

|

- Theories |

- Productive forces |

|

- Position |

- Disposition |

|

- Space |

- Development |

|

- Values |

- Social Practices |

|

- Narration |

- Historicity |

|

- Institutions |

- Social Relations |

Source: the author (2023).

Among the elements of the “ethical diamond” mentioned above, the present work will be dedicated to analyzing the elements theories and position (of the conceptual axis) and disposition (of the material axis), in order to demonstrate that, initially, the adoption of decrees known to be illegal and unconstitutional started from the adoption of biopower as a way to manage people’s lives, not using such decrees as normative means, but as security devices closer to research and statistics. This strategy, however, was only possible thanks to the position occupied by the Judiciary, as a reviewer of the acts of the Executive Power, and, in particular, its willingness to recognize the validity of illegal and unconstitutional acts from its adhesion to one of the proposals of public policy presented to face the Covid-19 pandemic.

4.1 Biopower

The theory aspect - in the ethical diamond - receives the following concept by Herrera Flores (2009, p. 125): “Theories: ways of observing a process or a thing and that allows us an idea about its characteristics”.

In the present case, it seems to us that the issuing of unconstitutional and / or illegal decrees was adopted as a government strategy.

In this sense, according to Foucault, from the eighteenth century onwards, absolute power, based almost exclusively on the will of the ruler and on the power of the law he edited, which gave or sovereign the power to “let live and cause to die”, was gradually replaced by biopolitics or biopowers8. In this sense, Foucault (1999, p. 131) conceptualizes:

[...] it was formed a little later, around the middle of the 18th century, focused on the species-body, on the body pierced by the mechanics of the living being and as a support for biological processes: proliferation, births and mortality, health status, length of life, longevity, with all the conditions that can vary them; such processes are assumed through a whole series of interventions and regulatory controls: a bio-politics of the population.

If before, the sovereign power was concerned with “making people die and letting them live”, with biopolitics the State’s objective is to “make them live and let them die” (Médici, 2011, p. 59).

In this new way of governing, the law has a secondary position and is superseded by other strategies that aim to ensure exercise in a more subtle way, inducing people to adopt desired postures almost imperceptibly. It is important to highlight, however, that according to Foucault, this power is never unique or centralized, being composed of micropowers that normally overlap and eventually concentrate in search of a common goal.

The research and statistics that, through the presentation of numbers and data that are often incomprehensible, fulfill the role that formerly belonged to legal texts with far-fetched and inaccessible language, are highlighted. The objective, as in the past, is to oblige (but now in a subtle way) the population to do or fail to do something, and, in this scenario, statistics and campaigns become the main technical factors of the art of governing:

[...] the population will appear as the government’s ultimate goal. For what can the government’s objective be? Not certainly to govern, but to improve the fortunes of the population, increase their wealth, their life span, their health, etc. And what instruments will the government use to achieve these ends, which in a sense are immanent to the population? Campaigns, through which action is directly on the population, and techniques that will act indirectly on it and that will allow the birth rate to increase, without people realizing it, or direct the flows to a certain region, etc. (Foucault, 1998, p. 289).

In this regard, it is important to highlight that in the case of decrees issued in the context of combating the Covid-19 pandemic, research is always preceded or succeeded, many of them with dubious technicality, which coincide with the illegal or unconstitutionally adopted measures. Thus, if the decree determines that elderly people are prohibited from exercising their right to come and go, the research presents the “advantages” of the elderly staying in their homes, isolated, dependent on the kindness of others to have access to food and other necessary for their survival (we speak of survival because, in some cases, even a dignified life has been denied).

Research is also widely used by biopower and, in this case, it does not matter whether its results are conflicting with reality or not credible. As an example, a survey released by Datafolha regarding the agreement of the Brazilian population regarding the adoption of a lockdown reached the incredible 60% favorable adhesion mark (Gielow, 2020), a data totally dissonant with the percentage of people who complied with the rules of social isolation, who did not increased from 50% in virtually no Brazilian state (Dolzan; Jansen, 2020). In this new scenario:

[...] the law would continue to have a certain importance, but the need to control new aspects of people’s lives would have required the adoption of new mechanisms to motivate them to adopt certain behaviors and to abandon others. In this sense, statistics would have gained unmatched importance, as it came to represent one of the main tools used by the government to support and disseminate research and advertising that started to induce social practices. In addition, statistics allowed power to appropriate life, not taking into account the individuality of each person, but based on the supposedly generic phenomena that link the lives of all people [...] (Dias; Oliveira, 2017, p. 257).

Thus, from the premises launched here, it seems to us that, although the heads of the Executive Branch are aware of the illegalities and unconstitutionalities that emanate from their fatal decrees, they ended up adopting them not as materially normative acts, but only as acts formally normative that, in fact, would fit better as advertising pieces, imagined not by jurists or those initiated in the lawful role, but by marketers more concerned with “selling” a product. They are imbued, in the logic of biopolitics, in “making people live”, but with the threat that an eventual lack of popular support can condemn the disobedient citizen to be the object of the State’s indifference, which can “let him die”.

In this new quality, the decrees are no longer normative acts and, therefore, would no longer be subject to judicial control, but to the control of the advertising market, which would assess its ability to convince people to adopt the measures it determines, or rather, he suggests.

A great example of this advertising concern with government acts and policy can be seen in the case of the flexibilities proposed by the Government of the State of São Paulo, starting on June 1, 2020. Initially, the State Governor used the expression “Smart quarantine” to name the future acts that it intended to adopt in order to guarantee the gradual opening of the São Paulo economy (Amorim, 2020). Probably alerted by his marketers that such an expression could give rise to the conclusion that the measures adopted until then were not “smart” (as, we even understand that they were not), he chose to name his new government policy “resumption” conscious ”, preventing any playful pun on your government strategy (R7, 2020).

The decrees as advertising pieces, however, only managed to maintain their survival thanks to the collaboration of the authorities responsible for precisely evaluating their validity, in this case, the Judiciary, a theme that we will deal with in the next item.

4.2 Position and disposition

Two other aspects of the ethical diamond allow us to demonstrate how the decrees limiting fundamental rights, despite being illegal and / or unconstitutional, were considered valid and continued to regulate people’s lives.

The first of these elements is the “position”, conceptualized by Herrera Flores (2009, p. 125) as: “a place that occupies itself in social relations and that determines the way to access goods”. In this sense, the organs of the Judiciary Branch were fully aware of their position in the social relations related to the measures adopted by the members of the Executive Branch, since at no time did they fail to analyze the various actions that were proposed questioning such decrees.

This praiseworthy position stems, as is known, from the adoption of the principle of non-avoidability of jurisdiction, enshrined in art. 5, item XXXV, of the Constitution (the law will not exclude injury or threat to law from the Judiciary’s assessment). The problem, however, arose due to the “disposition” that was adopted by the organs of the Judiciary.

The “disposition”, another element of the “ethical diamond”, is conceptualized by Herrera Flores (2009, p. 124) as “‘awareness’of the situation that is involved in the process of accessing goods and ‘awareness’ of how it works within that process”.

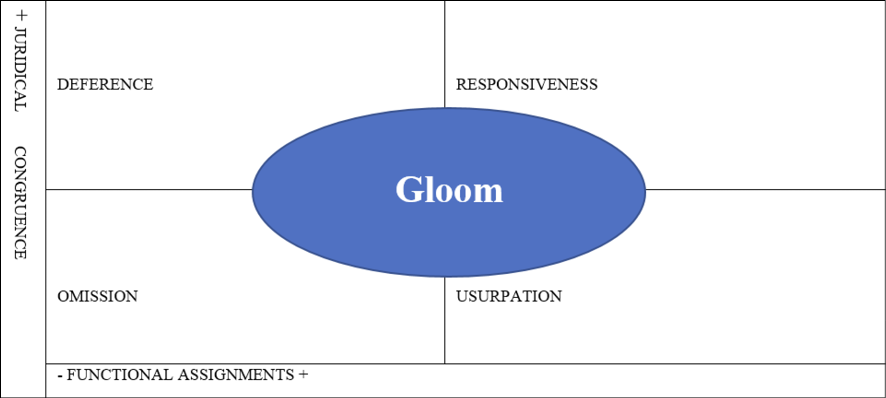

In this sense, using the classification presented by Oscar Vilhena Vieira (2018, p. 177), it can be said that the decisions of the Judiciary were deference to the measures adopted by the Governments of the States, of omission regarding the control of the constitutionality of the decrees and of responsiveness / usurpation in relation to the measures adopted by the Municipalities, as shown in the table below:

Image 1 – Constitutional stances

Source: the author (2023).

Initially, regarding deference and omission, the author brings the following concepts:

By deference, in the strictest sense, is meant the institutional posture by which the courts demonstrate a high degree of respect for the decision of the legislator that defined the content of a right or regulated its exercise by complementing or regulating the constitution.

[…]

Deference should not be confused with omission, which means the inability to comply with the fundamental obligation to “keep the constitution”. This omissive stance may be a result of the lack of authority, integrity, tradition or autonomy in the legal field in the political sphere, but it will always indicate that the Judiciary is failing to fulfill an obligation that was clearly conferred on it by the constitution (Vieira, 2018, p. 174-175).

In the case of decrees issued by State Governments, the Courts of Justice adopted a stance (provision, in the classification of Herrera Flores) of great respect for the content of their determinations, using, in most cases, meta-legal arguments to maintain their and omitting to analyze its constitutional validity.

Regarding the normative acts issued by Municipal Mayors that do not agree with the guidelines issued by State Governments, the attitude adopted by the Courts of Justice was, at times, responsive, and at other times, usurpation. For Oscar Vilhena Vieira (2018, p. 175), regarding responsiveness:

Responsiveness, in turn, is associated with the idea that the judiciary must be actively involved in providing answers so that the constitution and fundamental rights, in particular, are enforced to the greatest extent possible.

Responsiveness, however, according to the author, cannot be confused with usurpation, a situation that, unfortunately, ended up happening in some isolated cases. In this sense:

Responsiveness should not be confused with usurpation, in which the Judiciary advances, without due normative justification, on the functions of other powers, and not for the purpose of issuing a normative judgment on the validity of certain acts and rules in relation to the Constitution , but with the aim of replacing political or technical decisions made by other powers by their own technical or political judgments (Vieira, 2018, p. 175-176).

In this sense, when the São Paulo Court of Justice, even in the face of a decision by the Supreme Federal Court determining that the division of powers established in the Federal Constitution be recognized, it decides that the municipality will not be able to legislate on local interests, having to submit to the will expressed in a decree of the State Government, there is a deference of the Judiciary Power in the face of the State Government and a posture of responsiveness (or even usurpation9) in the face of the municipal government.

This stance (in the words of Oscar Vilhena Vieira) or disposition (according to Joaquín Herrera Flores) clearly demonstrates that the Judiciary ended up adhering to a (state) government policy and moved away from all the others that did not coincide with it10, omitting it even if to control the constitutionality of the decrees issued in the name of this government policy.

Conclusion

The poverty of reality cannot make us reckless with the Constitution and the rule of law.

The principle of legality is one of the most expensive historical constructions of our state model, to even illuminate democracy itself. It brought revolutionary constitutionalism with it and shaped the format of the rule of law.

The constitutional basis of rights, as the basis of constitutionalism, combined with the principle of legality, protected us from the discretion of the rulers, by establishing two great primates: a) that there is constitutional pre-formatting for certain rights, even if they do not make them absolute; b) that any restriction to these rights can only operate if it is provided by law and provided that the essential core of the law is protected.

This constitutional design prevents, at first, the frontal vilification of the law, even by law. And in the spaces where the law allows the establishment of contours, there is a need to guarantee the subsistence of the law.

What haunts us, however, is to imagine how such obvious constitutional bases were blindly torn apart, allowing, on a large scale, fundamental rights to be restricted by the force of secondary normative acts. And, more than that, the selective analysis that was used for such acts, often establishing discussions that totally ignore some assumptions.

Thus, when the Judiciary enters the contours of competence of one or another federative entity, it starts from the analysis of decrees as if they were laws, forgetting the insanity that would prevent the beginning of any derivation. That is to say, one should not argue over who is competent to deal with restrictions by decrees, simply because decrees cannot establish restrictions contrary to the law and the Constitution.

In the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, however, unconstitutional decrees limiting fundamental rights were widely used, not as normative acts per se, but as advertising pieces of government policy, real security devices, imposing a “do live and let die” in the service of biopower.

The prevalence of unconstitutional decrees, originating especially from State Governments, both over normative acts issued by the Federal Government, and by municipal laws and decrees, was only possible because such decrees were adopted not as normative acts but as an advertising piece, that is , a safety device or control mechanism at the service of biopower, but which only had its survival guaranteed, despite its illegality / unconstitutionality, thanks to a deference (disposition) posture towards them by the Judiciary, which, on the other hand, it omitted to control its constitutionality, and ended up acting responsibly / usurpation in relation to federal and municipal normative acts.

In addition to representing a serious violation of the rule of law and the principles that guarantee it, such attitudes, both from the executive and from the judiciary, represent a very serious precedent that, in the future, may be invoked to impose new and unconstitutional limitations on rights fundamental. Pandora’s box opened.

References

ALEXY, Robert. Teoría de los derechos fundamentales. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Politicos y Constitucionales, 2002.

AMORIM, Paulo. Doria anuncia ‘quarentena inteligente’ em São Paulo; veja como vai funcionar. FDR, 26 maio 2020. Available in: https://fdr.com.br/2020/05/26/doria-anuncia-quarentena-inteligente-em-sao-paulo-veja-como-vai-funcionar. Access in: 8 jun. 2020.

BORGES, Emerson. A Constituição brasileira ao alcance de todos. Belo Horizonte: D’Plácido, 2020.

BORGES DE OLIVEIRA, Emerson Ademir. A Constituição é o preço do combate à pandemia de Covid-19? Conjur, 8 abr. 2020. Available in: https://www.conjur.com.br/2020-abr-08/emerson-oliveira-constituicao-preco-combate. Access in: 23 jun. 2020.

BORGES DE OLIVEIRA, Emerson Ademir. Ativismo judicial e controle de constitucionalidade: impactos e efeitos na evolução da democracia. Curitiba: Juruá, 2015.

BORGES DE OLIVEIRA, Emerson Ademir. Curso de jurisdição constitucional: direito comparado e ideias para um novo STF. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris, 2017.

BORGES DE OLIVEIRA, Emerson Ademir; RAMOS JÚNIOR, Galdino Luiz; DIAS, Jefferson Aparecido. Princípios processuais e direitos fundamentais. Marília: Poiesis Editora, 2017.

DIAS, Jefferson Aparecido; OLIVEIRA, Emerson Ademir Borges de. O desemprego e o autoatendimento no setor bancário: entre o biopoder e a biopolítica. REPATS, Brasília, v. 4, n. 2, p. 253-270, jul./dez. 2017.

DOLZAN, Márcio; JANSEN, Roberta. Monitor aponta que média de isolamento social no Brasil é de 43,4%, Estadão, 15 jul. 2020. Available in: https://noticias.uol.com.br/ultimas-noticias/agencia-estado/2020/05/15/monitor-aponta-que-media-de-isolamento-social-no-pais-e-de-434-ideal-seria-70.htm. Access in:8 jun. 2020.

FOUCAULT, Michel. História da sexualidade I: a vontade de saber. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal, 1999.

FOUCAULT, Michel. Microfísica do poder. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal, 1998.

GARCIA DE ENTERRÍA, Eduardo. O princípio da legalidade na Constituição Espanhola. Revista de Direito Público, v. 21, n. 86, p. 5-13, abr./jun. de 1988.

GIELOW, Igor. ‘Lockdown’ tem apoio de 60% dos brasileiros, diz Datafolha. Folha de S. Paulo, 26 maio 2020, Available in: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2020/05/lockdown-tem-apoio-de-60-dos-brasileiros-diz-datafolha.shtml. Access in: 8 jun. 2020.

GOMES CANOTILHO, José Joaquim. Direito constitucional e teoria da Constituição. 7. ed., Coimbra: Almedina, 2007.

HERRERA FLORES, Joaquín, A (re) invenção dos direitos humanos. Trad. Carlos Roberto Diogo Garcia; Antônio Henrique Graciano Suxberger; Jefferson Aparecido Dias, Florianópolis, Fundação Boiteux, 2009.

KELSEN, Hans. Jurisdição constitucional. 2. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2007.

KELSEN, Hans. Wer sol der Hüter der Verfassung sein? Die Justiz, h. 11-12, v. VI, p. 576-628, 1931.

MÉDICI, Alejandro. El malestar em la cultura jurídica: Ensayos críticos sobre políticas del derecho y derechos humanos. La Plata: Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 2011.

MENDES, Gilmar Ferreira. Direitos fundamentais e controle de constitucionalidade. 3. ed., São Paulo: Saraiva, 2007.

MORAES, Alexandre de. Direito constitucional. 34. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2018.

PIEROTH, Bodo; SCHLINK, Bernhard. Grundrechte: Staatsrecht II. Heidelberg: C. F. Müller, 1995.

R7. SP: Doria anuncia ‘retomada consciente’ a partir de 1º de junho. R7, 27 maio 2020. Available in: https://noticias.r7.com/sao-paulo/sp-doria-anuncia-retomada-consciente-a-partir-de-1-de-junho-27052020. Access in: 8 jun. 2020.

VIEIRA, Oscar Vilhena. A batalha dos poderes. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018.

1 Doutor e Mestre em Direito do Estado pela Universidade de São Paulo. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7876-6530. emerson@unimar.br.

2 Doutor em Direitos Humanos e Desenvolvimento pela Universidad Pablo de Olavide; Mestre em Direito pelo Centro Universitário Euripedes de Marília. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3101-1621. jeff.bojador@gmail.com.

3 3 Depending on lessons from Moraes, the choice and maintenance of the monopoly of legislative activity with Parliament is basically due to three reasons: “it is the institutional seat of political debates; it is configured in a sounding board for the purpose of information and mobilization of public opinion; it is the organ that, in theory, due to its heterogeneous composition and its functioning process, makes the law not a mere expression of the dominant feelings in a given social sector, but the will resulting from the synthesis of antagonistic and pluralist positions in society” (Moraes, 2018, p. 44).

4 BVerfGE 58, 300 (336).

5 Individual rights and guarantees are not absolute. In the Brazilian constitutional system, there are no rights or guarantees that are of an absolute nature, not least because reasons of relevant public interest or requirements derived from the principle of coexistence of freedoms legitimize, albeit exceptionally, the adoption by state bodies of restrictive measures of individual or collective prerogatives, as long as the terms established by the Constitution itself are respected. The constitutional status of public freedoms, by out lining the legal regime to which they are subject - and considered the ethical substrate that informs them - allows them to apply legal limitations, designed, on the one hand, to protect the integrity of the social interest and, on the other hand, to ensure the harmonious coexistence of freedoms, since no right or guarantee can be exercised to the detriment of public or der or with disrespect to the rights and guarantees of third parties ”(STF MS 23.452, Rel. Min. Celso de Mello, j 16-9-1999, DJ 12-5-2000).

6 STF, Rel. Min. Marco Aurélio, j. 12-4-2012, DJe30-4-2013.

7 “The Municipality is competent to fix the opening hours of a commercial establishment”.

8 Although we understand that there are differences between the terms biopower and biopolitics, this article will adopt the position of Foucault, who did not differentiate the two terms.

9 The decision of the São Paulo Court of Justice could be classified as usurpation, determining that Law 8,543 / 2020, of the Municipality of Marília, regulating the operation of local commerce, could not contradict the decrees issued by the Governor of the State of São Paulo (ADI - Process 2122512-53.2020.8.26.0000).

10 It is not ignored that the system of checks and balances provided for in the State Constitutions determining that the appointment of Judges of Justice and Attorneys General of Justice may have some influence, even if indirect, on such decisions, but this topic is not the subject of this article.